Management strategy evaluation is a great framework and ABM should steal it!

Identification and policy

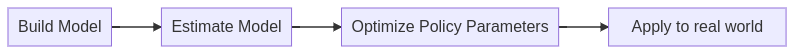

You want to manage a system, applying to it a policy that will maximize some ojbective you have. So you build a model of that system, estimate its parameters with data and then find the optimal policy given what you estimated. In my mind this is why we bother making models at all (although policy-making is conspicuosly missing both from “Why Model?” and “Different Modelling Purposes” ).

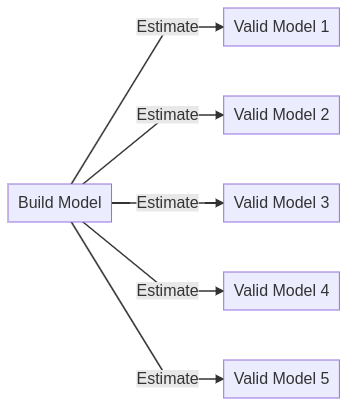

Imagine now estimation to be impossible. Maybe you don’t have enough data, maybe some parameters of the model are hard to identify, whatever. Now you are left with (infinitely?) many valid estimated models. We still want to do policy making; what do we do?

Well, the most common approach is probably to just add assumptions, making the model simpler or the data look more informative. At the end you are again left with a single valid model and you can go back at optimizing. Then spend the rest of your carreer sniping at everbody else who uses a different set of assumptions to pick a different valid model.

Another approach is to try something fancy like stochastic or robust optimization, looking for policies that incorporate model uncertainty in their suggestions. I have never seen a particularly effective example for it in ABMs however.

You could also try some “deep-uncertainty” methods like minimax, or scenario clustering. I find those techniques very hit and miss: sometimes very informative, sometimes giving you very obvious recommendations and sometimes just hiding the results in some fiddly hyperparameter (there are many ways to cluster scenarios and results vary significantly!)

Closed Loop policy

If right now you don’t know the state of the world, trying to come up with the “best” overall policy may be the wrong objective. You can’t know, regardless of modelling footwork.

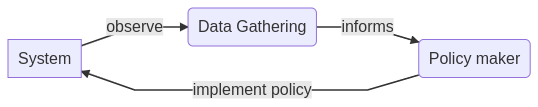

Rather we set up our policy to collect more data and act on it as time goes by.

This is an “adaptive policy” but it’s better to consider it as a closed loop where our actions affect the data we collect or the way the system behaves in ways that may be counter productive.

This is sensible, but by itself doesn’t actually solve the problem at hand.

After all this adaptive policy will depend on some parameters (how implementation changes as a function of data we have?) and if we want to find the optimal adaptation we are back at square one.

We are still stuck at needing to estimate the model to optimize parameters of the policy.

Management Strategy Evaluation

So finding the optimal policy is unfortunately still out of the question when we can’t estimate the model. In fact it’s even hard to define optimal under these circumstances (unless one policy/parameter-set always dominates all others).

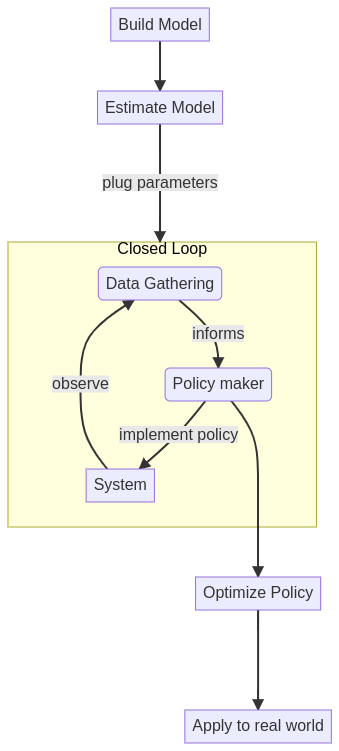

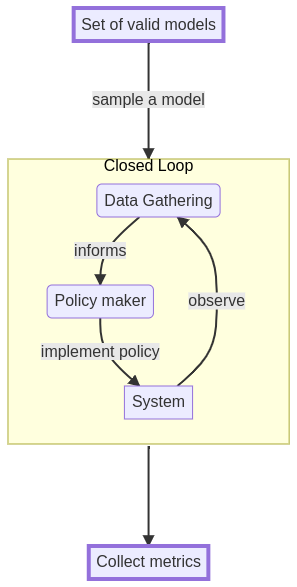

You can however still get a lot done. First, give up on estimating a single model and turn the process into being able to sample from the (possibly infinite) set of “valid models” at will. Then subject each valid model to the same closed-loop policy simulation and collect key metrics of what is happening at the end. Finally use these metrics to judge the quality of your policy or at least its vulnerabilities (i.e. what kind of valid models it does poorly in).

You collect all these metrics and then try to figure out how performance connects with the property of the models you sample (does a policy always perform very poorly when some model parameters appear in a certain way?).

And that’s really management strategy evaluation:

- closed loop policy simulation

- multiple candidate models of the system.

The main advantage here is that you separate the errors from not knowing the model, from the errors given the limited data you have and the errors due to implementation noise. +

One step further: ranking policies (and optimization?)

Management strategy evaluation ends up with a very qualitative whimper: we need to trawl through all the metrics to make some sort of sense of what is going on. This is quite anti-climactic.

If we are willing to sell our soul to Bayesianism however, we might be able to get some hard numbers and in fact return to optimal policy analysis.

Imagine that the models we feed into the management strategy evaluation are being sampled from the “distribution” of all valid models.

As the sample of valid model grows in size you can start averaging out the metrics the simulated policy outputs. This will converge somewhere because of the central limit theorem.

So now you can now associate to each policy (or policy parameters) the average metric. As long as you can keep sampling from the distribution of all valid models, you can rank (or optimize) policies again.

This is the approach from the DLMtoolkit for example.

Of course caveat emptor: the “distribution of all valid models” is likely just a complicated space generated by priors on the model parameters (which are usually of very poor quality): change those and the policy metric you are optimizing for will change accordingly (and sometimes massively so). It’s very likely that, as the number of parameters grow, you are just reciting your priors back at you.

All in all however, management strategy evaluation can both produce qualitative and quantitative insights when identification issues make every other approach invalid. To a great extent this is already done in the agent-based modelling community but I like the formal definition that fisheries’ literature has set up.